About

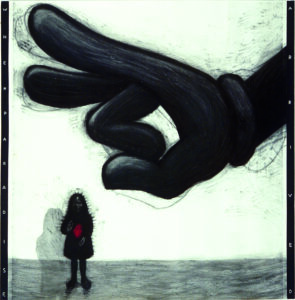

In 1967, a landmark exhibition of “Funk art” opened at Berkeley’s University Art Museum, featuring works by Northern California including Bruce Conner, Joan Brown, Peter Voulkos, Jim Melchert, William Wiley, Robert Arneson, Roy de Forest and David Gilhooly, among others. In the exhibition catalog, curator Peter Selz painted the Bay Area as a “sweet land of funk,” writing that: “Funk art, so prevalent in the San Francisco-Bay Area… is at the opposite extreme of such manifestations as New York ‘primary structures’ or the ‘Fetish Finish sculpture which prevails in Southern California. Funk art is hot rather than cool; it is committed rather than disengaged; it is bizarre rather than formal; it is sensuous; and frequently it is quite ugly and ungainly.” Ever since, the label “Funk” has been commonly applied to art and artists of Northern California.

The notion of “Funk art,” however, was controversial from the start, as many of the artists included in Selz’s exhibition sought to distance themselves from the designation. At a symposium held to mark the exhibition’s opening, artists registered their dissent in radical ways—one poured a glass of water over their head, while another responded to Selz’s questions by launching a shoe into the audience. In their view, the art on display was too diverse to fit under such a restrictive label.

In subsequent decades, so-called “Funk” artists continued to defy the designation. Conner, for example, vociferously rejected the assertion that his funky assemblages, produced in in the late 1950s, were part of a coherent school of “Funk.” William Wiley, who was christened a “Metaphyisical Funk Monk” by ArtNews, also resisted the label. The work produced by Wiley and his circle shared the same absurdist and playful spirit as others included in Selz’s show; however, they had a more literary bent, and were consciously engaged with art historical traditions such as Dada and Surrealism. Roy de Forest and his circle, similarly, chose an alternative label for their idiosyncratic movement, penning a “Nut Art Manifesto” in 1972.

The history of art in Northern California is more textured and varied than the simplistic term “Funk” might suggest. This exhibition explores the history and limitations of the descriptor, and asks: if Bay Area art cannot be understood as the product of a coherent school of “Funk,” how should it be understood? What common attitudes or themes connected the broad array of works produced in the postwar period? How should we understand the legacy of Bay Area art, and its impact today’s emerging artists?

Funk art is hot rather than cool; it is committed rather than disengaged; it is bizarre rather than formal; it is sensuous; and frequently it is quite ugly and ungainly. — Peter selz

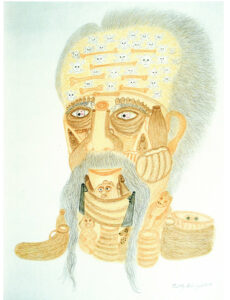

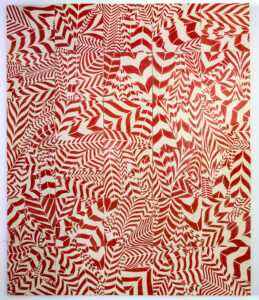

artworks in sweet land of funk

return to vignettes

di Rosa Downtown: Betty and Clayton Bailey | June 7 – September 7, 2025

Descarga Cubana | July 12 – September 28, 2025

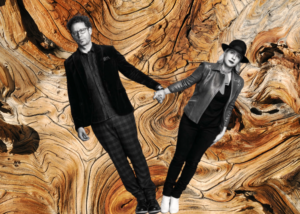

Ancient Wisdom for a Future Ecology: Trees, Time, and Technology | January 20 – April 11, 2026

Jim Melchert: Where the Boundaries Are | October 18, 2025 – January 3, 2026

Far Out: Northern California Art from the di Rosa Collection | August 2 – October 4